“What kind of genius is Rosamond Purcell? Is she an artist? A scholar? A documentarian? A living cabinet of wonders? Her originality defies category…”

— Jonathan Safran Foer

Murre eggs nestled in cotton that appear to have been decorated by an overzealous Abstract Expressionist, a blanched piranha charging ahead in a glass jar of orange-tinged formaldehyde, a cast off typewriter transformed by time into an octopean tangle of rusticles. From luscious large format Polaroid prints to objects rescued from obscurity, the empathetic, evocative, and multifaceted work of the photographer and conceptual artist Rosamond Purcell (b. 1942) explores the ill-defined interstices between the unsettling and the sublime, the beautiful and the bizarre, the natural and the manufactured. As a body of work, it lays bare humanity’s desperate desire to collect and make sense of it all.

Over a career spanning some fifty years, Purcell has collaborated with paleontologists, anthropologists, historians, museum curators, termite experts, and even a scholar-magician to illuminate and explore the shifting boundaries between art and science. She has found some of her greatest inspiration in long-overlooked storage spaces in natural history museums across the world and in the hills and the shacks of a 13-acre junkyard located in an otherwise picturesque Maine coastal town. Purcell’s six decades of work, while brilliantly varied and resistant to easy classification, speaks eloquently to the artist’s persistent interrogation of the ways in which humanity has and continues to attempt, often fruitlessly, to understand the world around it. The barriers of logic and reason that we erect to make order out of chaos are exposed as porous and unreliable in Purcell’s work, an oeuvre that encourages its viewers to dwell in the nebulous spaces in between, to see things, in the words of Minor White, ”not only for what they are but for what else they are.”

This exhibition, Purcell’s first retrospective, will reflect the breadth of the artist’s career from the late 1960s to the current day and will include over 150 of the artist’s photographs, assemblages, collages, and installations. A pioneer of fine art color photography and an inspiration to a generation of artists from Mark Dion to Sally Mann, Purcell’s constant evolution and interest in exploring the precariousness of existence as expressed through the ways in which time haunts the living and renders the recognizable unrecognizable, positions the artist as one of our most powerful interpreters of the human condition.

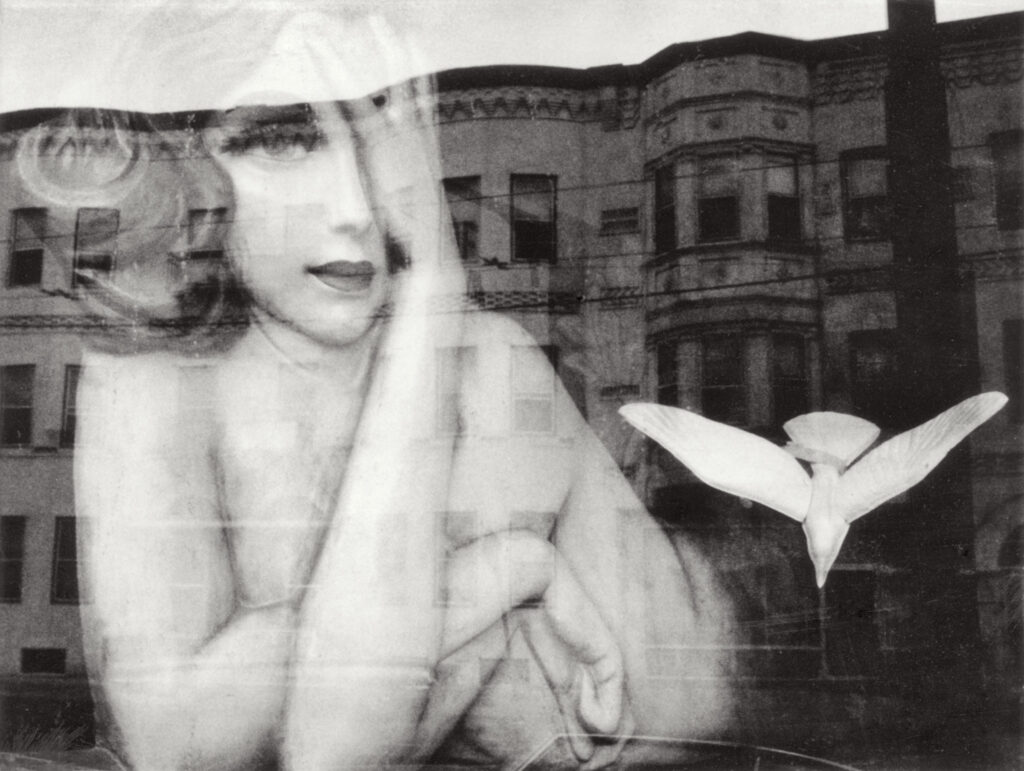

In bringing these photographs into pairs and then into short sequences several themes emerged. Although I have no conscious metaphorical or symbolic intentions, and although each picture was taken for its own sake with no other in mind, there are recurring ideas which do intrigue me. I am interested in illusion, in camouflage, in spaces between shapes (and between photographs), in double portraiture, and in ambiguity.

I was surprised at how the buildings across the street and the mermaid came together in the photo. I learned to make use of the flattening of foreground into background—the cross against the stone wall and the woman in the patterned dress.

The photographs included here were made over a period of five years. There is nothing new under the sun as far as subject matter is concerned, and my taste in old cars, mannikins, dolls, and people may reflect certain photographic conventions of the times. It is the tension I can bring to bear on these subjects which matters to me.

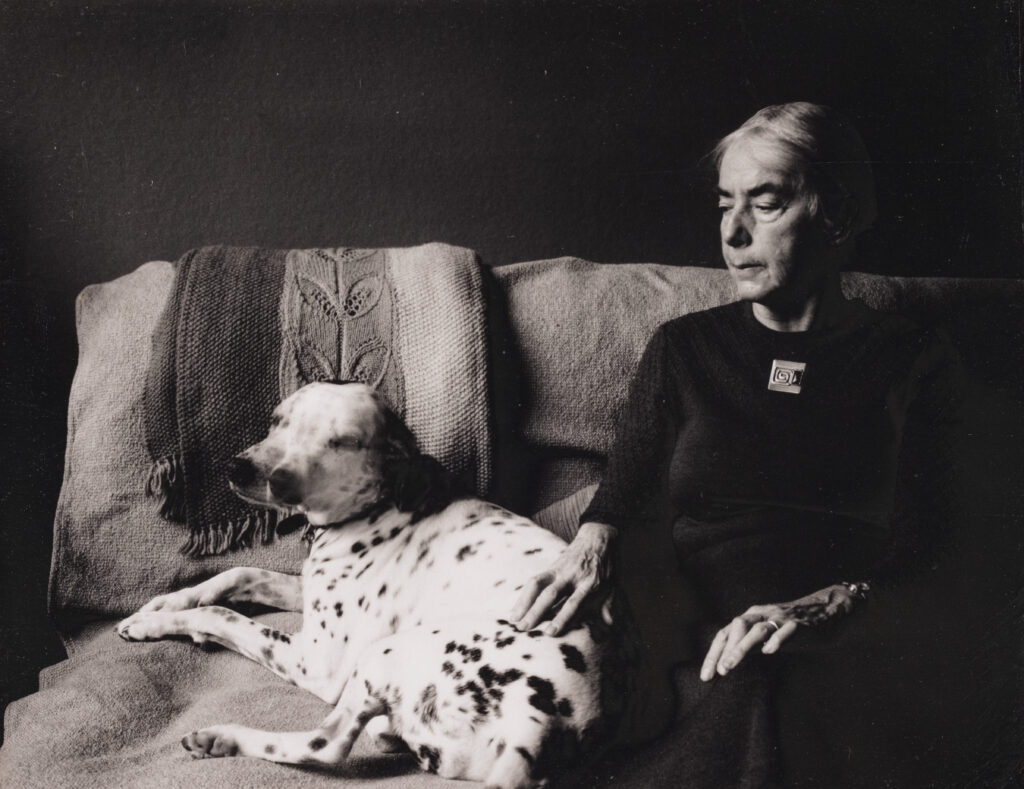

I did not anticipate that the dog would shake her head while her owner did not move. An ancestor of this dog appears in a Civil War photograph by George N. Barnard and James F. Gibson. Seen at a distance, the head of a white dog with dark spots moves from side to side.

Often, I depend on the appearance of objects and people rather than on internal inspiration to stir me into action. I use whatever I can of shapes, light, and time as elements in composition. And I pay strict attention to composition on the assumption that if the appearance is satisfying to the viewer, emotional involvement might then become possible.

I would have been quite content to work in black-and-white film if an incidental discovery had not introduced me to the possibilities of working with color. The Thinnest Layer is the evidence. It happened quite naturally, the way working with Polaroid films always seemed to happen. First, using the view camera, I took the usual black-and-white photograph (4 x 5 Type 52 film), and because it was underexposed (not to say unremarkable) I did not apply the plastic coating to protect the delicate surface and so guarantee longevity. At a later date, standing near a skylight, I noticed that silver had built up in the shadows of the discarded print, and, by tipping it towards natural light, reflected colors became visible. Here is the record of that effect, recorded onto Polaroid color film.

Before our younger son was born, I thought about evolution. I knew very little at that point except that monkeys were closely related to men. Fed up with telling friends and strangers where to stand and how to look, I retreated to the copy stand with a collection of damaged ambrotypes and, layering them with torn scraps and animal stickers, I made a collection of hybrid beings, followed by portraits expressing states of mind.

In the winter of 1981, after at least a year of going through institutional hoops, the curator in the mammal department extended a guarded welcome. As long as I followed the rules: filled out a record—including Latin name, collection number, and date the specimen had entered the museum, in addition to the date and time of my visit—it was OK to photograph the disarticulated skeletons, flattened skins, or “wet specimens” (preserved in formalin or alcohol), all stored in heavy wooden cabinets. The older skins—many over a hundred years old—preserved with strong chemicals were repellent but somehow it did not matter whether I liked them. It was everything to do with the following through of an idea and above all, even in this dark place, with the importance of using natural light.

Around this time, I was using a type of Polaroid film that simultaneously yielded black-and-white positive prints along with traditional negatives. The white cotton-stuffed mouths in the positive print appear dark and open, as if screaming, in the negative print. This second photograph with its irradiated chiaroscuro became essential when, in later years, I needed more expressive images to include in collages and other images about World War I.

I used Polaroid films for two or three years before learning how to print normal negatives in a darkroom. I had not intended be a photographer; Polaroid turned me into one. I learned to work from print to print, and stopped when I got a good one. I wasn’t concerned with multiples or editions. To this day, although the concept of producing multiples of images did come up when working with the 20 × 24 camera and is still now an option, I shy away from making editions. The fun for me is still in getting the single picture. But with Polaroid films one could improvise. Because the results were immediate, one could work from print to print rather than from wish to dream to hope. For years, of course, I used conventional film with 35 mm and 4 × 5 cameras, and now, digital cameras. For direct seeing, it feels more like Polaroid. The layers between seeing and receiving are thinner again.

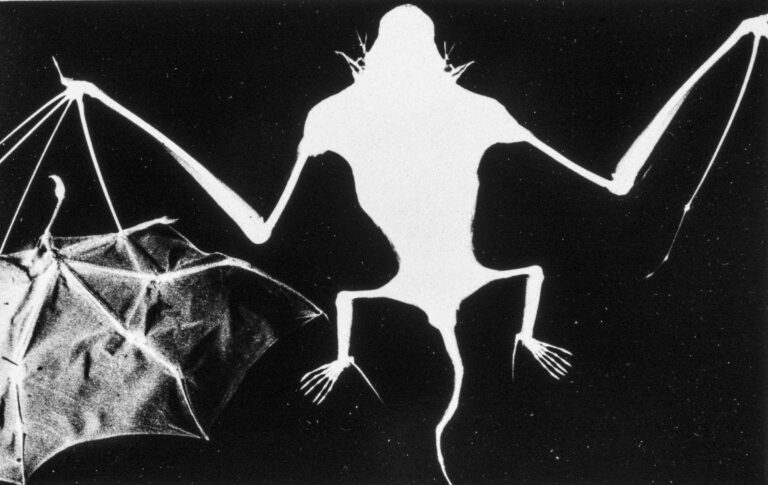

Bats look like pigs, horses, foxes, mice. They are reminiscent of Chinese dragons, of figures by Hieronymus Bosch, of medieval carvings of souls in hell. The wings of these bats were translucent as parchment and sometimes more fragile. Combined with X-rays (also kept, alongside the specimens, in the Mammal Department at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology) these photographs have as much to do with the properties and techniques of a scientific collection as they do with associative revelations about bats. Selective production of negative rather than positive photographic prints reinforces the perception that, for many of us, bats are poorly visible—elusive, nocturnal, mostly inaudible, flickering rather than fixed.

By the time photographers were invited by the Polaroid Corporation to use its special 20 x 24 camera, I had been collecting ruined objects from Owls Head, Maine for a few years. Owned by one man, William Buckminster, the thirteen acres of detritus became a rich source for pieces of scrap metal, ruined books, broken sewing machines, and ancient bricks. On a recent trip, I had come across six-paned windows and screens piled high and sunk into soft marshy ground.

My first chance to use the camera came in 1982. I chose as models a few large monkeys borrowed from the Museum of Comparative Zoology, along with a favorite gibbon. I drove them across town, packed in two old family suitcases. In the elevator up to the studio, a passenger, noticing their weight, asked, “What’s in there? A bunch of corpses?” “Yes,” I replied, stepping out. To be fair—I was also bringing along a few props, culled from Buckminster’s yard: electrical cords, heavy rusted springs, left-over screening, pieces of scrap from merchant ships, and cement lobster-pot weights.

Purcell has played upon our affinity for faces in her brilliant refurbishing of an old and tattered reverse-painted glass chessboard. She left the dark squares as she found them but festooned the white squares with a variety of complex overlays, mostly faces, drawn from a wide range of sources.

The more you look, the more you see, as our programmed preferences search out their intended targets. Look hard enough, and you will also find unintended faces in the unaltered dark squares—for oval shapes with appropriate blobs and dots often appear in random arrays and our mental machinery for recognizing faces then performs the translation (try row two, squares one and seven; or row seven, square four). Looking again, I can find a face on almost every dark square (look at the sultan in row six, square three). Doesn’t every cloud bank include a camel?

T.H. Huxley described our struggle to comprehend nature as a battle of wits: “The chessboard is the world, the pieces are the phenomena of the universe, the rules of the game are what we call the laws of Nature. The player on the other side is hidden from us.” In our ignorance, and with our limitations, we do indeed see nature as through a glass darkly—but perhaps, someday, face to face.

—Stephen Jay Gould

In the domains of the scientist and the curator, the death of an organism is the beginning; it strips away the layer of life. Other layers of information may then vanish with each stage of dissection—the skin from the bone; the bones from the skin; color or opacity from the tissue; or fluids from the vital organs, arteries, and veins. Irrelevant layers are discarded as the scientist seeks a proper vantage point for his work—be it a study of the vascular system of a squirrel monkey, an analysis of the cavities of an elephant skull, or a taxidermic version of a three-toed sloth (with internal padding added to reanimate the skin for the pleasure of the museum-going public). What the viewer to the collections sees then is always partial, sometimes vestigial, and to the nonscientist, often mysterious.

As a photographer I am attracted to zoological collections by virtue of their fragmentary state. Partially eroded or effaced surfaces appeal to me, as would an ancient piece of fresco,a piece of Egyptian linen with faint hallmarks, or a piece of text eaten by termites.

The Museum of Comparative Zoology holds thousands of ichthyological treasures from Brazil. The fish in this very jar were perhaps caught and pickled by William James himself, but as he writes, not with much joy.

The right angle, time of day, and all other ephemeral

“rightness” for an eloquent photograph is a one-time thing—no matter how the light comes in, it lingers for minutes, not hours. But the light is not the only thing that changes. Recently, at least twenty-five years after I took this photograph, I returned to the museum’s department of ichthyology hoping once more to see the head of this particular piranha, open jaws showing ominous blunt teeth, rising between and above the tails of its fellow fish in the orange-colored preservative bath.

Nothing ever stays the same. About twelve years ago, the alcohol in the specimen jars from the Thayer expedition was changed and the sunset colors are now gone. While both species and subspecies of piranha remain in their original groups, in the process of decanting and refilling the glass containers, their orientations inevitably shifted. As I have no record of the collection number for that particular piranha or for its species, there will be small chance of finding it again. Unlike James searching in murky or clear running rivers to scoop up nature’s bounty, I have no authority to go spelunking into the jars for museum data or even to catch a glimpse of the memorable face of this fish among so many pallid corpses.

From the beginning of my collaboration with Stephen Jay Gould, we agreed that images of natural history as traditionally conceived of—noble or rapacious beasts in ideal poses in ideal landscapes—did not interest us. Nor did ruler or coin inserted to show the scale of a bird wing or the tail of an armadillo. At the time we were working, it was the eloquence of the fragments of collected science that we wished to examine—fur, feathers, bones, teeth—those broken bits hidden from public view. As collectors ourselves, he of rare works of paleontology and natural history and I, too, of old books and ruined objects—we relished the aesthetic and storytelling details behind the not-so-obvious. Our work began to thrive, not, as one might think, on wordy strategic planning, but on many independent observations recorded by a photographer and contemplated by a scholar who read the photographic evidence in terms of morphology, of the convergence of forms, sometimes simply for the names of things. We established a fluidity over the years, I took up the camera and went out hunting. He would then extract a story or principle from the evidence. The first times I gave a photograph to Stephen and he returned with text, I was amazed. He had legitimized the photograph as something other than an aesthetic effect. I knew what I was looking at, of course, the femur of a zebra, the ribs of a giraffe, but I had not known before what else the film had captured or what one could deduce from studying these details. I chose the subject in the first place. It required Stephen, as a scholarly detective, to see it further.

The so-called “eye spots” on the backs and wings of many insects may serve several possible functions. In some species they loom large, as if truly the eyes of a much bigger creature—and may thereby scare predators away. In others, they lie at an expendable periphery, attracting a predator’s attention to wing tip and the air beyond—and not to the vulnerable body. In any case, the enormous variety of circles, bars, and splotches invites our own playful interpretation, whatever the function (if any) for the insects that carry them. One naturalist found in moth and butterfly wings all the letters to reproduce a line of Roethke’s poetry— “All finite things reveal infinitude.” Here, arrayed like cartoon early worms poking their heads above the ground, we see dark spots at the wing tips of Samia moths facing each other in two rows.

—Stephen Jay Gould

The museum has its methods, but with all due respect, the system often has a way of closing out the cosmos from which each creature came. The urgent need, as ecosystems collapse, for scientists to gather statistics on each animal—natural history, geographical range, and conservation status—tends to make the ode, the painting, the prayer, seem extraneous. Scientific data are attached to bull and butterfly alike, but there is not enough room on the card or in the catalogue to report how the philosopher, the villager, the forest dweller, or the poet saw the animal walk, crawl, zigzag, or soar.

This roll call on paper of Leiden’s extinct and endangered animals and birds has been supplemented by a few rare specimens from other museums. And yes, they are all, obviously, dead—but how these dead can dance! Although life passes, patterns and forms remain, and there is nothing like bringing beautiful feathers, bones, and fur to the light of day. In the grassland of New Zealand, the quail flew up in seconds. In the museum, the same quail are motionless, but the light is always moving—and daylight, changing minute by minute and hour by hour as it falls across the feathers, reanimates the birds. The effect of feathers, bones, scales, or horn bathed in light and the study of seasonal changes in the quality of light are crucial to this, my style of photography.

The Norfolk Island kereru was first described and last seen in 1801. This large subspecies of the New Zealand pigeon lived on Norfolk Island, which lies in the Tasman Sea northwest of New Zealand. Apparently, it could not survive the deforestation and hunting that accompanied the arrival of Europeans. Pigeons also suffered when New Zealand was colonized, but unlike the population on Norfolk Island, the New Zealand birds managed to survive.

—René Dekker

As a photographer, I have long been drawn to natural history and anatomical collections. I am intrigued by traditional museum conceits: classification, juxtaposition of words and objects, the relationship of the collectors or curators to their collections, in short, the grey area between a rational scientific system and human idiosyncrasies.

Private and institutional collectors share the same instinctive hunger: to seek, to find, to classify. I’ve heard of a man in the deep country who has collected furniture, clothes, paper, and arranged them systematically (by class of object) along the road and through a field. He visits his collection daily, checking, sorting, talking, handling every part to be certain nothing is out of place, nothing gone awry. No conscientious collection manager in a big city museum would do otherwise.

I’ve heard of a bottle collector who had recently realized he had a passion for books. He explained, “I’m digging now, but I’m still shallow,” which expresses for me that particular sweet uneasiness which is an essential part of the predator/collector’s mind on the prowl. True collectors never touch bottom.

Mounted primates in early museum collections are sometimes posed holding fruit or nuts. The articulated skeleton of this monkey, seated on a painted table among a shower of crabapples in a makeshift garden, holds a small, page-furled notebook from the museum archives. The notebook, found a long time ago on a beach, was kept in the collection as an instructive example of the action of waves and tide. Its pages, foliated like layers of ancient rock, evoke Darwin’s famous text on the fragmentary nature of the fossil record: “I look at the natural geological record, as a history of the world imperfectly kept, and written in a changing dialect; of this history we possess the last volume alone, relating only to two or three countries. Of this volume, only here and there a short chapter has been preserved; and of each page, only here and there a few lines.” The elements in this Dutch still life combine in a symbolic language of transitory gestures: the passage of years (or waves), the brief visible manifestations of crabapples in that summer and in that place, and the attempt to reanimate a sentient primate by placing a historical document in its bony hand.

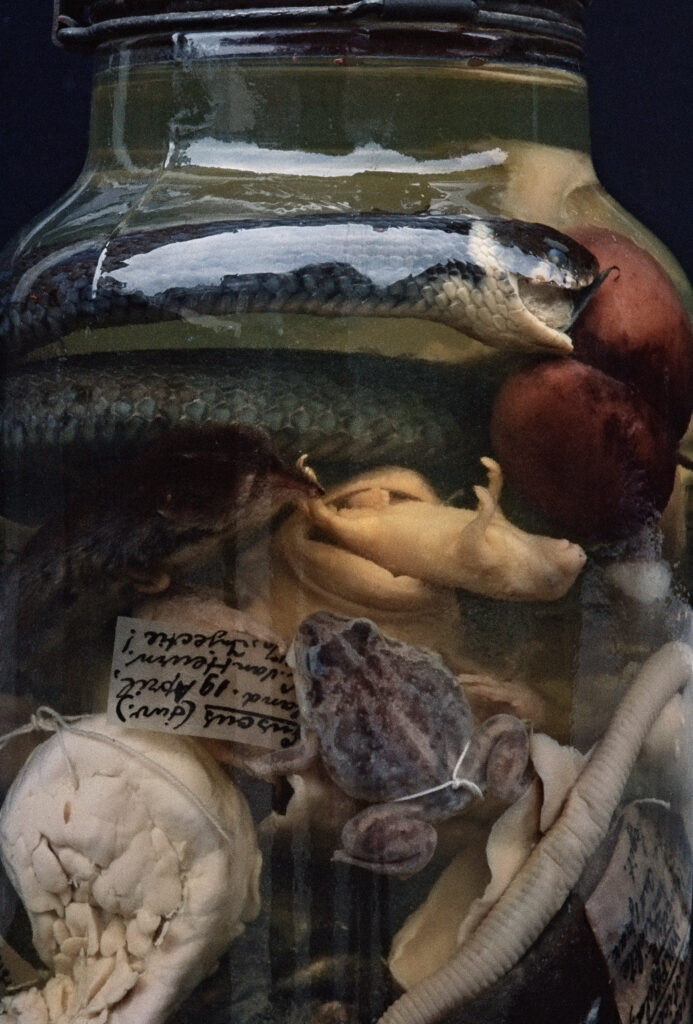

The specimens in this jar were placed there by the collector Willem Cornelis van Heurn in the mid–1950s and have passed into the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden, Netherlands, unchanged in their taxonomic jumble, waiting for a patient curator to untangle the cat guts from the toad, the shrew from the fetal pig, the double apple from the snake, and to assign each a proper classification within the order-driven institution: the moles with the moles, the frogs with the frogs, the snakes with the snakes. Under this “same-kind together” system, it does not do to preserve animals from disparate biological groups under the same glass lid for eternity.

Whatever the technical difficulties of photographing an object through glass, they become insignificant when transparent and translucent surfaces permit a veritable lexicon of illusion. Preservative liquids of various viscosities contrive to grant subjects unexpected depths, faint or dramatic reflections, absent, displaced, or exaggerated detail, and some room, a window often or here, a courtyard to cross over and present itself head-on in the same plane as the subject, expands the sense of place and brings relief to what might otherwise seem an obsessively myopic or clinical view of objects not traditionally considered artistic in nature. Around the rim of the jar in the bright, reflected space, the walls and turrets and sky of the inner courtyard of the museum building can be seen, signifying perhaps the institution’s dominion over all such collections, however confused, however unclassified, however lowly.

On the road to the Owls Head lighthouse, we came across a colorful pile of lobster buoys, several weathered buildings, and then, high behind the old-growth tree, we saw it: jagged hills of scrap metal looming like glinting crests of water or like dismantled dinosaur parts. In heaps and mounts and prodigious hills the junk surged above us. We took our cameras, tripods, and water bottles and walked into the hills. The ground was covered with lobster traps, household pots and pans, piles, and stacks of wooden shutters. It was the most covered ground I’d ever seen. On the periphery of the mountains, a small unsmiling person appeared and said—not much. His name was William Buckminster and he much have said it was okay to walk around, to take pictures, and to buy whatever we found outside or from a house marked ANTIQUES, because we did. I don’t remember much photography from that day; the sun was hot and most of us drunk on the novelty of rural eccentricity and unfathomable chaos. The steep mounds were tight-packed and tumbling; I could feel the pressure of even more hidden under the slopes and the foundations of the buildings.

Over the years, until he went out of business in 2000, Buckminster became less dour in his manner toward me, telling stories that revealed the considerable depths of knowledge he had acquired as an observer of human and animal behaviors and as a self-taught expert in the early industrial history of the state of Maine. Although he was the proud owner of an early nineteenth-century brass foundry and decidedly a collector, he always seemed a somewhat reluctant businessman—wary of his visitors’ intentions and scornful of the vanities of mankind. Of a competitor in junk down the road, he complained, “His is just an accumulation, mine is a business.”

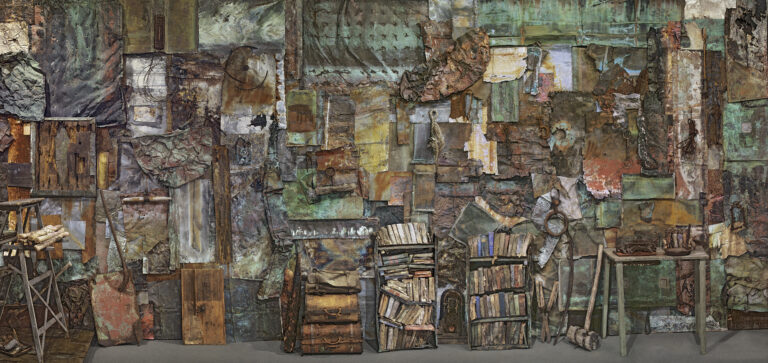

I fabricated a twenty-foot-long wall from scrap gathered at Buckminster’s. It includes much copper sheathing from merchant ships. This wall has traveled to several museums as part of the exhibition Rosamond Purcell: Two Rooms, which included the reconstruction of Ole Worm’s cabinet of curiosities.

—

Buckminster’s land, like the coastline of Maine, is slowly sinking and his number of objects shrinking; but paradoxically, even as he owns less, the ongoing disintegration of whatever remains contributes to the surface area, augmenting the overall measurements and hence acreage of his domain, every day. As the years went by, there was never less to see. And as human eyes are capable of focusing on only one piece of a heap at a time, my work at Buckminster’s was never done. The overall field of awareness of two eyes working is not quite one hundred and eighty degrees. The area of actual resolution within which one can clearly identify an object is about two degrees. If only I had a fish-eye lens for eyes or a gazing globe from an ordinary garden.

This hybrid structure, half book half nest, made by a mouse out of syllables and straw, was lifted decades ago from a trench-like hole in Owls Head, Maine. Hidden beneath dry grass is the title, Flying Hostesses of the Air.

A great number of these artifacts, as if squeezed and contorted like lumps of metamorphic rock, appear at the tail-end of familiarity. They have been chipped from the matrix, not just of one man’s holdings, but from the almighty “thingness” of our all-American world. I decided that order might come from such chaos, if I were to follow and untangle some threads.

I admit to an attraction to and tolerance for the most friable things. Patina, rust, and almost total evaporations do not distress me. Cracks, warpings, holes, and shards add unpredictable and welcome complexity to many objects, turning the tedium of manufactured clones into singularities. I use groups of them as metaphorical chunks in an imaginary, yet cohesive collection of pseudo-historical artifacts. Often, in dissolution, a manufactured object assumes a more natural character.

Only the few know the sweetness of the twisted apples.

—Sherwood Anderson, Winesburg, Ohio

Perception of the anomalous is bound to cultural expectation. We have searched the world quite thoroughly since medieval times, vaporizing mythological monsters as we go, even as collective memory seems to crave their imagined presence. We have inherited a rich fictional past that cannot be denied; rumor, illusion, dreams, and hearsay amuse us, while science, if serious, generally is less “amusing.” A unicorn has more glamour than any benighted rhino or narwhal.

Unfathomable for those who are not in physical pain to understand the dilemma of human beings for whom pain does not cease—pain of twisted bones, of missing limbs, of misshapen features. Impossible to know the emotional state of those people for whom, as the photographer Diane Arbus said, “life’s trauma has already happened.”

I am attracted to the lenses in antique projectors, shadow puppets on a wall, and to Cocteau’s film Orphée, where the dead pass through mirrors as if through water.

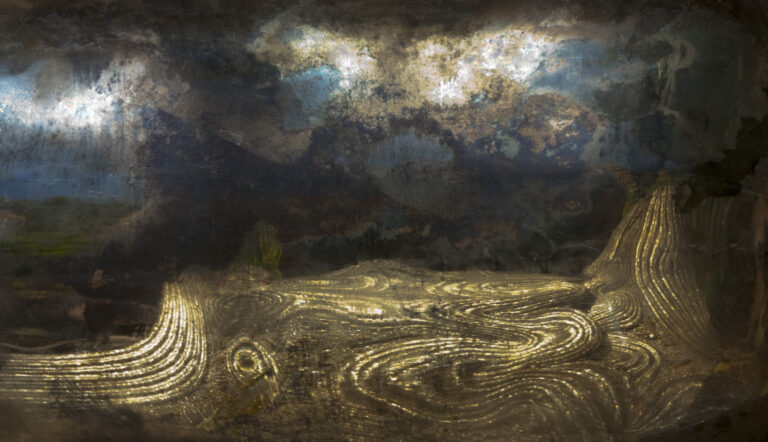

Windowpanes, specimen bottles, Victorian glass plates and mirrors—I work with these for the objects they hold, the shadows they cast. Twelve years ago, I found an early twentieth-century apothecary jar double-glazed and light-tight; it had originally held fabric dyes.

Months earlier Michael Witmore at the Folger Shakespeare Library had suggested a collaborative project inspired by Shakespeare; as the photographer, I searched for a looking-glass way into the spirit of the age. From another place, down the road, I bought a few more bottles and took them to a meadow in northern New Hampshire, where I hoped they would deliver up alchemical reflections worthy of Lear or Lady Macbeth.

I turned them toward the light. Scarred by history, anamorphic in their reflecting properties, the bottles did not accommodate a single view without constantly changing it. Photographing into double-layered glass was like recording stills from a time-lapse film. The camera is a free-form kaleidoscope. Chronology races and all becomes liquid and out of place.

Time is like water, objects almost boneless, and whatever is fished out will not swim by again. All rules for previsualizing a conceptual photograph are without force when at play in this stream of the hybrids. I do not get “better” at working with the mercury bottles. From time to time, I do get lucky.

To-day the French,

All clinquant, all in gold, like heathen gods, Shone down the English; and, to-morrow, they Made Britain India…

—Norfolk, All is True (Henry VIII), 1.1

We step with awe into the vast and chilly stronghold of eggs and nests at the Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology in Camarillo, California. In state-of-the-art cabinets, the specimens, often accompanied by remarkable accounts of field data, are laid out with utmost care and concern. There are many ways to “read” this collection of ornithological holdings, which represent nest-building and egg-laying strategies of birds from every possible species and clutch size, egg shape and pattern, as they vary within each clutch and between closely related species of birds.

In the case of the great egret, John James Audubon made a drawing only—he did not ever make a full-scale print. When I consider a beautiful skin of the great egret from the Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology, I imagine that this is the very bird in the drawing by Audubon. This is, of course, just a wishful thought. According to the Foundation’s records, this great egret, an adult male, was collected on March 14, 1991, twenty-eight kilometers south of El Boliche, Ecuador. It does not matter for the sake of this story who collected it. Here it is, white bird travelling, sui generis, on a long flight.

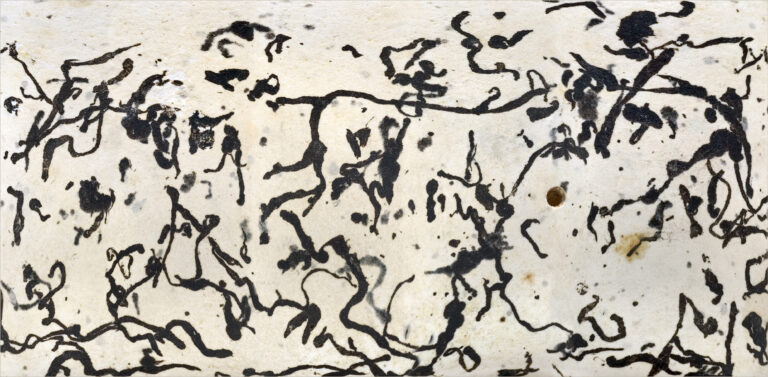

The calligraphic effects so pronounced on blackbird eggs may appear over the entire surface of the eggs of the guillemot or common murre, dancing and twisting in lines reminiscent of Japanese writing or Chinese brush painting. It was impossible to see the surface of this egg at one glance overall. I photographed around the circumference one section at a time. At home, we assembled the pieces into a “Mercator” projection. By stitching the segments, we created a large mural of acrobatic monkeys swinging from vines, a young chimp riding a unicycle, gibbons in free-fall. But then, looking again—a “vine” becomes the outline of the back of a bull, emerging like an ancient creature from the walls of Lascaux. I began to think and to write about the connections between avian and human art . . .

Moors, bishops, lobsters, streams, faces, plants, dogs, fishes, tortoises, dragons, death’s heads, crucifixes—everything a mind bent on identification could fancy . . . There is no creature or thing, no monster or monument, no happening or site in Nature, History, Fable or Dream whose image the predisposed eye cannot read in the markings, patterns and outlines found in stones.

—Roger Caillois, The Writing of Stones, 1985

The animals don’t move, but the light moves,

the best light is brief

and the collection manager is often rustling in the wings.

The tide warns me.

Vita brevis, sweet life.

On view through December 31, 2022 at the Addison Gallery of American Art.