Scottish born photojournalist Harry Benson CBE came to America with The Beatles in 1964 and in his words, “never looked back.” In the decades since, the award-winning photographer has demonstrated incredible range. He photographed Civil Rights marches and the Watts Riots, was on the scene when Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated, and covered conflicts in Kosovo, Bosnia, and the Gulf War. The only photographer who has photographed the last 13 U.S. presidents from Dwight D. Eisenhower to Joe Biden, Benson has also turned his lens on everyone from Mohammad Ali to Queen Elizabeth II. His photographs of historic events, political figures, and luminaries have been published in major magazines including LIFE, The Daily Express, Time, Vanity Fair, W, Newsweek, French Vogue, Paris Match, Forbes, The New Yorker, People, Quest, and The Sunday Times Magazine. The subject of a 2015 documentary, Harry Benson: Shoot First, Benson’s work has also been published in numerous monographs including the recently released Paul celebrating the 80th birthday and career of Paul McCartney.

Building on the Addison’s holdings of works by Benson and amplified with loans from the artist, this exhibition focuses on four powerful photo stories from the 1960s: the building of the Berlin Wall, the Beatles’ first American tour, the James Meredith March Against Fear, and the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy. These photographs not only catapulted Benson’s career, but also incisively capture defining moments of this tumultuous period in history.

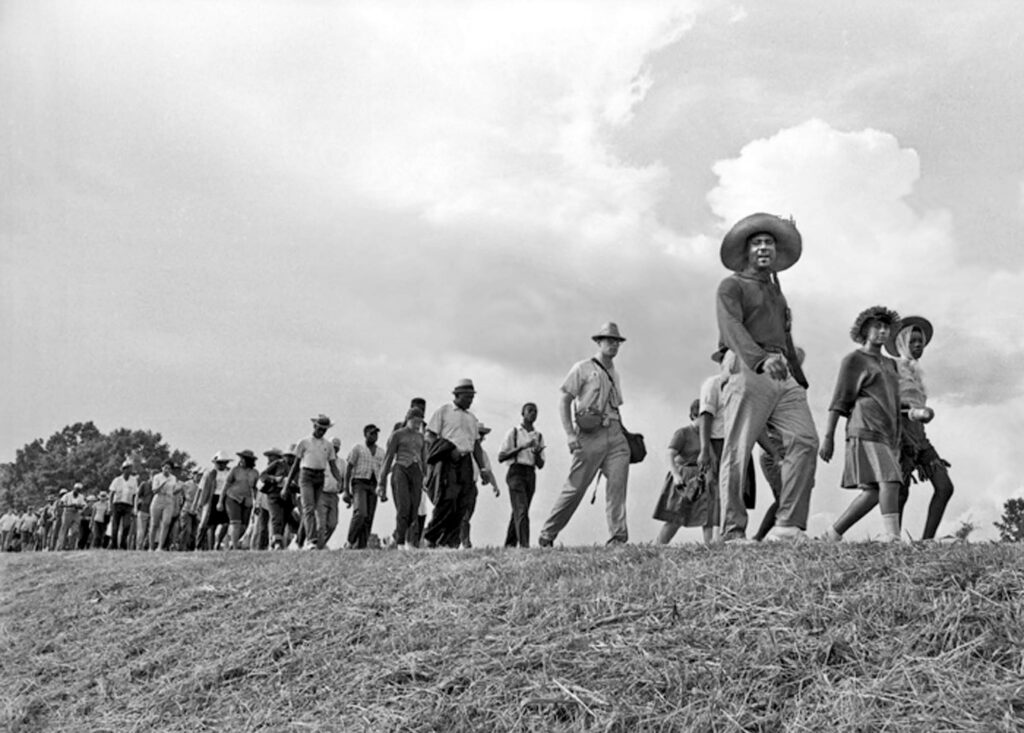

James Meredith March Against Fear

James Meredith, who had been the first black student admitted to the University of Mississippi in 1962, set off to walk the 220 miles from Memphis, Tennessee to Jackson, Mississippi in 1966. Meredith’s “March Against Fear” was intended to encourage black citizens across Mississippi to vote. But on the second morning of the march, Meredith was shot by a sniper Klansman. Despite initial press that reported Meredith’s death, the activist survived and was later able to rejoin his march. Leaders including Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and John Lewis also joined in support. Benson marched with them, covering the story for The Daily Express, London.

James Meredith’s Freedom March in Mississippi in 1966 was one of the things I am glad I covered. I think the reporters who marched alongside must feel the same…

Each night I would go to some dingy motel and develop the day’s take in the bathroom, shut in there with an enlarger. I had to blackout the room and put on a red light I had brought with me…I splashed about with the chemicals and would come out with a few prints that I would transmit on a portable machine I hooked up to the telephone in my room. It went beep-be-be-be-beep over and over. If Vic Davis, the reporter on the march with me, called in the middle of the transmission with a “hello, old boy,” I’d have to start over. That part of the job was maddening. It took hours, sometimes all night. And we thought we were on the cutting edge. It was definitely not instantaneous e-mail.

—

We passed many onlookers as we marched. Some heckling, some singing the Southern anthem “Dixie” and waving the Confederate Flag.

—

I have always said the 1960s were when America had a nervous breakdown. One night we tried to pitch our tents in a schoolyard in Canton, Mississippi, even after the city councilmen had ruled against it. Shortly after we arrived, a colleague of mine, Tony Delano, said, “Harry, turn around.” I turned to see a line of State Highway Patrolmen putting on their gas masks and coming toward us, tear gas and guns in hand. They neared our group and lobbed the tear gas. A cloud of smoke enveloped us, and I got a whiff of it. As I was retching and stumbling away, a young highway patrolman looked me straight in the eye and gave me a little tap on the backside. I was taken in by a black family who gave me cold towels and some water.

—

On April 4, 1968, amidst rising racial tension, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was shot while on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. America was shocked, stunned, and again pitched into the nightmare of violent death and public agony, not five years after President John F. Kennedy’s assassination in Dallas.

Mrs. King and her four children flew from Memphis back to Atlanta with Dr. King’s body for burial. As Dr. King’s body was being taken from the plane, there was just a moment when the family came together in the doorway.

—

With police sirens wailing and buildings smoldering around me, I happened upon the scene of man lying dead in the street in the early hours of the morning. The policeman casually told me there was a curfew and “that includes you…” The second night we went out, I found the police frisking another Watts resident standing next to the Second Baptist Church and words rang out in irony: “God is Love.”

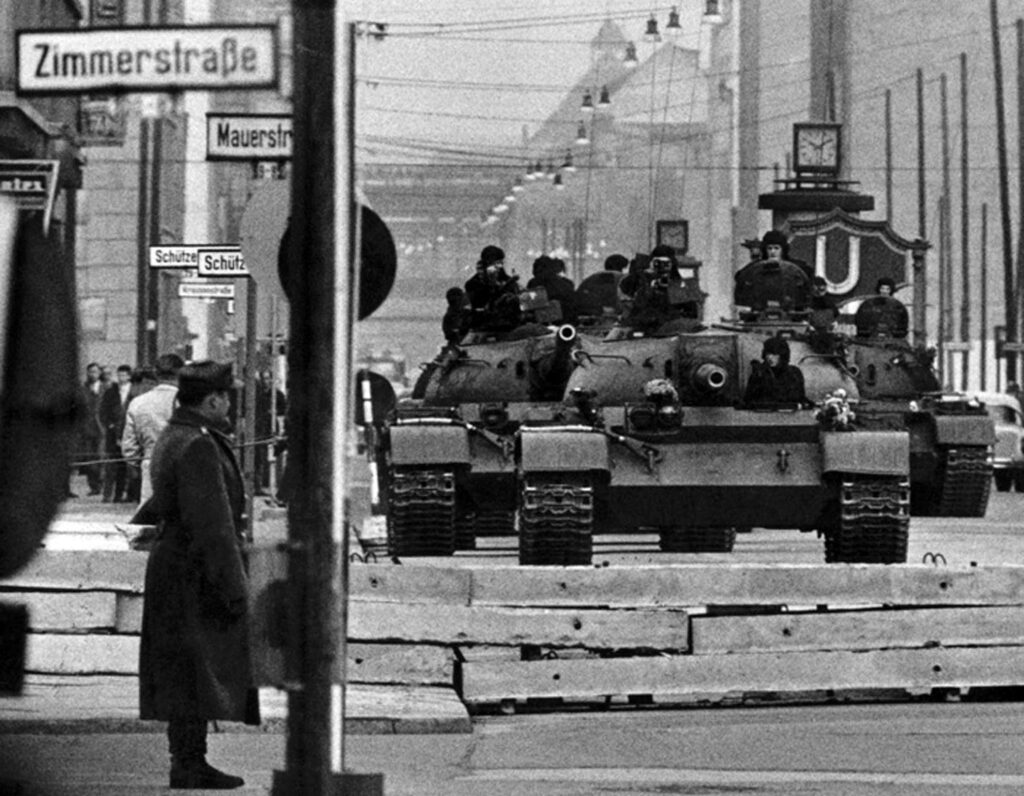

BERLIN WALL

In August 1961, Benson, then a Fleet Street photojournalist in London, heard something was happening in East Berlin. He took the first flight to Germany and was there the day the Berlin Wall was erected. A concrete and barbed wire barrier, the Wall would serve as both a physical and ideological divide separating East and West Berlin and came to stand as a symbol of the Cold War. Benson was also there, photographing crowds cheering, when the Wall fell in 1989.

Coincidence plays a large role in a photojournalist’s life, and I was lucky that a very good Fleet Street reporter named Donald Edgar was on the same flight with me from London that Sunday morning. He spoke perfect German. He suggested we go directly to find the mayor, Willie Brandt. We got to Brandt’s office just as he was leaving, but he waited for me to take a photograph and to answer some questions from Edgar. He let us go around with him in his jeep for a while to survey the horrendous situation—Russian troops encircling his city. The picture is important to me because it was taken on the day that mattered—August 13, 1961—the day the Berlin Wall went up.

—

I flew into Berlin the night before the wall came down as there were reports the wall was about to come down . . . Here East German soldiers watch as West Berliners hand out flowers to East Berliners crossing over into the West, November 9, 1989.

—

Walking around trying to see what was happening, I turned a corner and came upon this row of Russian tanks waiting for orders to move. I backed up slowly and went the other way.

THE BEATLES

Benson was initially reluctant to photograph a relatively new group called the Beatles in Paris in 1964, as he was supposed to go to Africa on another assignment. However, after meeting the band and hearing them play, he recalls thinking, “I’m on the right story.” The Beatles song “I Want to Hold Your Hand” hit No. 1 on the U.S. charts, and Benson accompanied them on their inaugural American tour. His photographs capture the sheer joy and optimism that would be embraced as Beatlemania and that helped lift America’s morale just 11 weeks after John F. Kennedy’s assassination.

At about 3:00 A.M. after a performance, the Beatles’ manager, Brian Epstein, came in to tell them “I Want to Hold Your Hand” was number one on the U.S. charts, which meant they would be going to America to perform on the Ed Sullivan Show. They were elated with the news. I had seen them have pillow fights before and when I suggested it, they all said it was a silly idea. Then John sneaked up and hit Paul in the head and the fun began.

—

It seemed John and Paul could compose anywhere. They would wander over to the piano, sit down, and start playing, taking no notice of what was going on around them. Here in their George V Hotel suite, they were composing “I Feel Fine.” George and Ringo wandered over and started to join in. It was fascinating to watch how intense they were while creating a song.

—

Beatlemania was spreading, and this was to be their first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show… As everyone knows, they were sensational. The frenzied audience with girls crying and screaming in mass hysteria drowned out their singing. This became the norm for all their appearances.

—

Before their second Ed Sullivan Show appearance, I took the Beatles to meet Clay [later Mohammad Ali], who was training for his upcoming fight against Liston… Clay, dancing around the ring, pointed to Paul and shouted, “He’s pretty, but I’m prettier.” He made them line up, lie down, and literally stole the show. This had never happened to the Beatles before. They were taken aback and furious with me afterward, saying, “Clay made a fool of us, Benson, and it was all your fault.”

—

On February 7, 1964, Pan Am flight 101 from London landed at New York’s JFK Airport. “I Want to Hold Your Hand” had become number one on the U.S. charts only a few days earlier. I had arranged with them to turn around and look at me as they exited the plane, but in the excitement of the moment, they forgot. I called out for them to turn around. Ringo heard me and reminded the other three and I took the photo. Since the crowds of screaming fans had been kept away by the New York police, I didn’t bother to develop and wire the photos to London. Years later, photographer Jonathan Delano was helping me and came across the undeveloped roll of Tri-X film. I am glad he found that roll, for the photo is important to me because it was taken on the day we all arrived in America for the first time.

—

After an interview with British journalist Maureen Cleave in which Lennon said the Beatles were more popular than Jesus, an uproar from the Bible Belt ensued. DJs refused to play their music on the air, stores refused to sell, and fans were burning their records. Lennon was very upset when I arrived in Chicago and tears welled up when he said, “Why did I open my big mouth?” The other three Beatles were annoyed and John made a formal apology. Later he was much more cocky about it. And, of course, some people think he was right.

—

At the Beatles walked out of the shadows onto the field, the roar of the crowd was deafening.

ROBERT F. KENNEDY

On June 5, 1968, less than three months after the murder of the civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., Robert Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles as he campaigned for the presidential nomination. Benson, who had been covering the campaign, was on the scene when the bullet hit. With an unnervingly close approach and a startling immediacy, Benson captured the frantic moments as aides rushed to the wounded candidate and as wife Ethel Kennedy, who was pregnant with the couple’s eleventh child, raised a shielding hand.

When asked about how he was able to separate the emotion of this horrific event and his duties as a photographer, Benson said: “I just knew it was historic, and I said to myself, ‘Let me mess up tomorrow, but not today. This is for history.’ So I put the camera up to my face and just started photographing. I was there to cover a celebration which turned into a tragedy before my eyes.”

The heat was stifling as the train slowly crept along, carrying the body of the slain senator and presidential candidate. Thousands of mourners lined the tracks, some with flags, others just standing, crying. Senator Robert F. Kennedy was to be buried near his brother, President John F. Kennedy, in Arlington Cemetery.

—

Words cannot express the horror and sadness of the situation. The room was moving, people were screaming, vomiting, crying, banging their heads on the wall shouting, “Not another Dallas.” The emotional shock to everyone there was tremendous…

One campaign worker stood dazed where the slain senator had fallen, and another placed her boater hat on the pool of his blood after the ambulance had taken him to the hospital.

—

Bobby Kennedy announced he was running for President on St. Patrick’s Day in 1968, and he marched up Fifth Avenue in the parade. People wanted to touch him and he would dive into the crowd and shake hands. At one point, he looked up, pointed his finger, and smiled. I followed his gaze and saw Jackie and John John with their heads out a Fifth Avenue window. Bobby knew they would be there. I photographed him that day and was on the campaign trail for the duration. There was a camaraderie among the press corps traveling with Bobby. You always got a photograph before the end of the day. I know it was manipulative, but he made you feel like one of the inner circle, and it worked. The press and people loved Bobby.

—

I started not to go to the Ambassador Hotel that night because it was evident that Bobby had won the California Democratic Presidential Primary, but I decided should go anyway. The campaign workers were chanting,

“Bobby, Bobby,” and “Sock it to ‘em, Bobby,” and the revelers were singing

loud songs. The mood in the room was jubilant when, at almost midnight, Senator Kennedy stepped to the podium at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles to give his victory speech. He thanked everyone for their support. A roar from the crowd ensued as he gave the victory sign and said, “And now it’s on to Chicago and let’s win there.”

When he left the podium, I started to go out of the way I had come in, but

it was so crowded I decided to follow the senator as he headed toward the back entrance that would take him into the kitchen on that tragic night. I was a few feet behind when I heard a girl scream. I knew instinctively what had happened. We had stepped out of happiness into hell.

On view September 1, 2022 – January 30, 2023 at the Addison Gallery of American Art.